Abstract

Indonesia’s fiscal system is trapped in budget absorption logic—treating year-end spending as success, even when it creates no returns, no reinvestment, and no compounding effects. This liquidation mindset produces five decay processes: allocation without return, disbursement without flowback, year-end syndrome, no retention or reinvestment, and velocity decay. The result is predictable: high absorption rates above 90% but stagnant GDP growth around 5%. Ministries act like spenders, not stewards, rewarded for liquidation rather than value creation. Without capital velocity, public spending becomes a treadmill—motion without progress. Fiscal governance must evolve from bookkeeping to stewardship, from disbursement to multiplication. Otherwise, Indonesia’s growth ambitions will remain structurally impossible, blocked by a system designed for compliance—not creation.

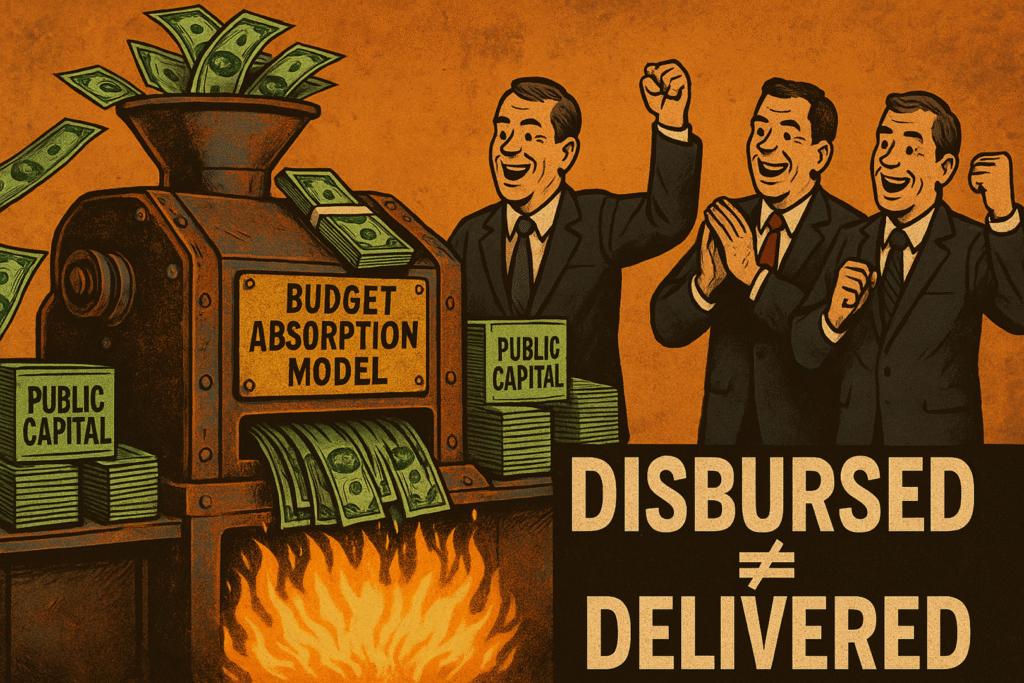

For decades, the Indonesian state has run on a simple premise: as long as we spend the national budget before the end of the year, we are doing our job. This model, known as budget absorption, has become a sacred metric inside ministries and agencies. But here’s the uncomfortable truth:

Absorption is not performance. It is not even strategy. It’s liquidation.

It doesn’t create value. It doesn’t multiply capital. And most dangerously, it kills the one thing that actually drives national wealth: capital velocity.

To understand how Indonesia’s economy can grow sustainably, we must dissect not only what is done, but why it is done. Budget absorption is not merely a technical issue — it’s a doctrinal failure. It reveals a deeper rot in our economic model: one that prizes accounting optics over capital logic. Indonesia’s fiscal architecture, dominated by absorption logic, follows a predictable 5 decay processes.

1. Allocation Without Return

Funds are often disbursed according to political cycles, bureaucratic formulas, or historical patterns—rather than any rigorous assessment of expected returns. For example, a 2023 World Bank study found that only 22% of public investment projects in low- and middle-income countries are subject to cost-benefit analysis before approval. Ministries are frequently judged by how much they spend, not how much value or revenue they generate. In the European Union, over 60% of regional development funds are allocated based on historical spending patterns, not performance metrics. This means capital isn’t allocated for velocity or impact—it’s allocated for optics.

When allocation is disconnected from outcomes, the budget becomes a performance, not a strategy.

The U.S. Government Accountability Office (GAO) reported in 2022 that nearly $200 billion in federal funds were allocated to programs with little evidence of effectiveness. This creates perverse incentives: proposals are written not to solve problems, but to ensure money moves. Value creation becomes secondary to budget absorption. Agencies prioritize “spend ability” over viability. The real question—“What will this capital return?”—is rarely asked.

2. Disbursement Without Flowback

Once funds are spent, the loop is closed. There’s no equity, no stake, and no reinvestment model. In fact, less than 10% of government programs globally have formal mechanisms to track or capture financial returns on public investments (OECD, 2023). There is rarely a system in place to measure, report, or recycle returns into future programs. This is not how sovereign capital should operate—it’s how a giveaway program works.

In capital markets, a fund that deploys capital without any yield is considered defunct. Yet in public finance, over 80% of government spending is evaluated solely on disbursement rates, not on measurable outcomes or returns (IMF Fiscal Monitor, 2022). The prevailing fiscal mindset equates spending with success. There’s no concept of capital recycling, no feedback loop, and no flywheel effect to amplify impact. Even worse, any surplus or return that does materialize is typically absorbed quietly into general revenue, with little transparency or reinvestment.

For example, a 2022 review of infrastructure projects in Sub-Saharan Africa found that less than 5% of completed projects had mechanisms for reinvesting user fees or operational surpluses into maintenance or new projects (World Bank, 2022). This lack of flowback means valuable public capital is dissipated rather than multiplied.

3. Year-End Syndrome

The infamous Q4 panic: as the fiscal year draws to a close, ministries scramble to spend unused funds before December 31st. This phenomenon is widespread—according to a 2023 OECD report, up to 30% of annual government expenditure in member countries occurs in the final quarter of the fiscal year. The rush leads to hurried project approvals, compromised procurement quality, and a reluctance to pursue innovative or complex solutions. The system punishes under-absorption, not under-performance.

In the private sector, wasting capital can cost you your job. In the public sector, civil servants are often rewarded for fully disbursing budgets, regardless of actual outcomes (IMF, 2022). This syndrome isn’t a glitch—it’s the operating system. Auditors and evaluators focus on disbursement rates, not on the quality or impact of spending. The obsession with budget realization turns civil servants into project fire-fighters, prioritizing short-term liquidation over long-term planning.

A 2022 study by the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that federal agencies spent an average of 38% of their annual contract funds in the last two months of the fiscal year, often resulting in lower-value purchases and minimal scrutiny. This year-end spending surge undermines efficiency, discourages innovation, and erodes public trust.

4. No Retention, No Reinvestment

Any unspent budget is seen as failure. Any return generated is untracked and uncelebrated. According to the OECD (2023), over 85% of government ministries in member countries are legally required to return unspent funds to the central treasury at year’s end, with no mechanism to carry over or reinvest surpluses. Ministries are prohibited from building long-term capital loops, leaving them dependent on annual injections with zero compounding effect.

Capital doesn’t flow. It drips, and then it dies.

Imagine a business that reinvests none of its profit, tracks none of its output, and must beg for capital each year regardless of performance. That’s the reality for most public sector agencies. A 2022 IMF survey found that fewer than 10% of public institutions globally have formal systems for tracking and reinvesting operational surpluses or efficiency gains. Instead of rewarding prudent management and retention, the system punishes it. Surpluses are erased, not celebrated; efficiency is penalized, not incentivized.

The result is a chronic lack of institutional memory, innovation, and growth. Ministries become trapped in a cycle of dependency, unable to build reserves or invest in long-term improvements. In contrast, high-performing sovereign wealth funds—like Norway’s Government Pension Fund Global—reinvest returns annually, compounding their value and delivering sustainable benefits for future generations (NBIM, 2023). Most ministries, however, are locked out of this virtuous cycle.

5. Velocity Decay

Each fiscal year starts from zero—no momentum, no acceleration, and no institutional memory of how capital can multiply. The result? A stagnant economy disguised as a functional one. In Indonesia, for example, annual budget absorption rates consistently exceed 90%, yet average GDP growth has hovered around 5% for the past decade, with little evidence of compounding impact from public investment (World Bank, 2024).

Velocity decay means that even in years of high budget realization, we remain structurally slow. According to the Asian Development Bank (2023), only 12% of Indonesia’s public investment projects are designed with multi-year compounding effects in mind, compared to over 40% in high-performing economies like South Korea or Singapore. Because capital isn’t compounding, it’s evaporating. Public spending becomes a treadmill—a lot of movement, but no real progress.

Part of the problem lies in political short-termism.

Many ministry leaders optimize for quick wins, not long-term returns—because their tenure is politically timed. As a result, fiscal planning becomes reactive, not strategic. Despite the existence of long-term national blueprints crafted by Bappenas and strategic agencies, these plans are often ignored or under-executed. There is no fiscal doctrine that links short-term decisions to long-term national outcomes. This lack of capital velocity and reinvestment means opportunities for transformative growth are lost. The Ministry of Finance’s own 2023 review found that less than 8% of completed government projects led to follow-on investments or measurable productivity gains. Instead of building on past successes, each year’s spending is disconnected from the last, erasing any chance of cumulative progress.

Root Cause: Misaligned Fiscal Doctrine

Indonesia’s fiscal system is still designed for a post-colonial administrative state, not a sovereign capital engine. Ministries act like spenders, not stewards. Finance is treated like bookkeeping, not architecture. As long as ministries are rewarded for disbursement, not return, Indonesia will be stuck in fiscal adolescence. We are not governing capital. We are emptying it. Like a spoiled heir burning through inheritance, rather than a founder building enterprise value.

A Call to President Prabowo: Absorption Logic Will Block 8% GDP Growth

Dear President Prabowo.

If we maintain this fiscal architecture, Indonesia will never reach 8% GDP growth.

Why?

Because 8% growth requires:

- A capital multiplier effect that compounds investment across sectors

- A fiscal engine that prioritizes return, not just expenditure

- And a governance mindset that scales capital strategically, not administratively

The current absorption model was never built for growth. It was built for control, legacy, and compliance. But Indonesia now aims to lead in Southeast Asia and beyond. That ambition is incompatible with a system that drains capital velocity year after year.

Mr. President, your vision is bold. But boldness needs scaffolding. If we keep the current system, your 8% goal will be politically desirable but structurally impossible.

We must rebuild the fiscal engine.

We must align ministries with capital performance.

We must replace absorption with multiplication.

The time to act is now.