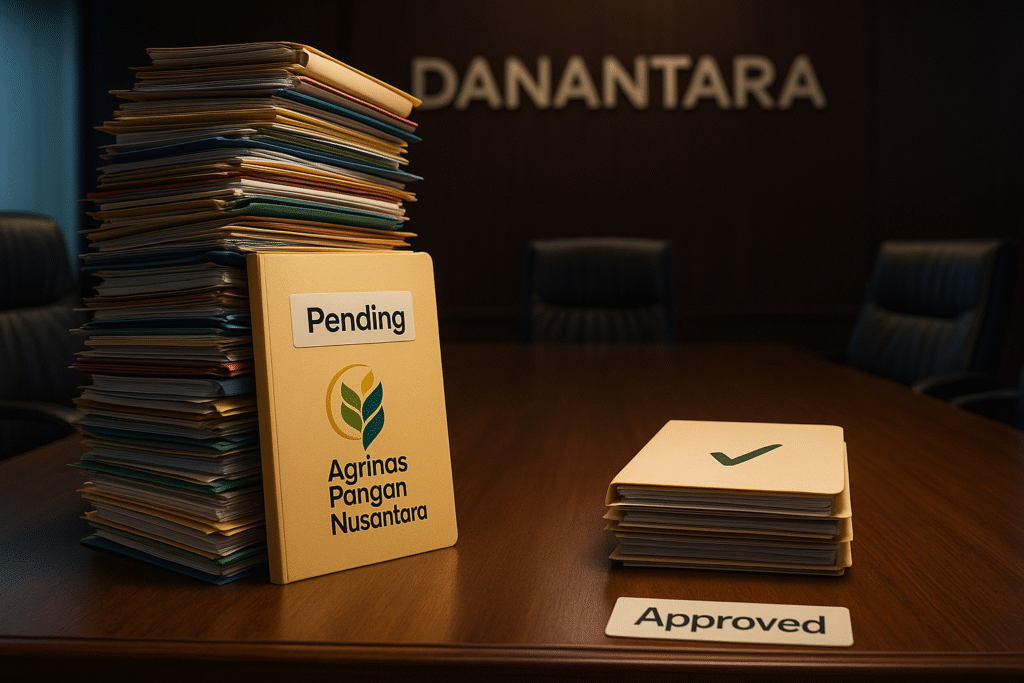

“Stacks of proposals don’t build power. Capital discipline does. Danantara waits, because sovereignty isn’t rushed.”

Abstract

The resignation of João Mota from Agrinas Pangan Nusantara has been framed as bureaucracy or misalignment, but the real issue is capital sequencing. Agrinas, rebranded from PT Yodya Karya in 2025, lacks deep agricultural track record and its pre-feasibility studies remain unclear on IRR, costs, or GDP multipliers. Meanwhile, Indonesia’s food estate push involves multiple actors, reducing urgency for Danantara to prioritize Agrinas. At the same time, Danantara is consumed with SOE restructuring and quick-win, high-ROI projects to establish credibility. This isn’t abandonment—it’s timing. Agrinas may still matter, but discipline dictates sequencing before symbolic approval.

The recent resignation of João Mota, CEO of Agrinas Pangan Nusantara, has drawn headlines and sparked debate over Danantara’s approach to project funding. Some see this as a sign of bureaucratic inefficiency; others view it as a signal that strategic priorities are being misaligned. But when examined through the lens of capital allocation discipline, the story is less about dysfunction and more about sequencing.

To understand the dynamics, we need to look at five interconnected factors: the nature of Agrinas itself, the economic clarity of its proposed projects, the broader food estate landscape, Danantara’s current institutional focus, and its overall project selection mechanism.

Agrinas Establishment & Track Record

Agrinas Pangan Nusantara is a newcomer in Indonesia’s agribusiness landscape. Officially rebranded in February 2025, the company emerged from PT Yodya Karya — a state-owned engineering consultancy with decades of experience in construction and design services, but none in large-scale agricultural operations.

This transformation was part of a wider state-owned enterprise (SOE) restructuring effort, shifting Agrinas’ mandate from engineering to agriculture to align with the government’s food sovereignty agenda. However, a rebrand does not immediately translate into operational capacity.

Agrinas currently operates as an institution still in early-stage organizational build-up. It is forming teams, building supply chain relationships, and developing sector-specific expertise. While the ambition is notable, its lack of historical operational experience in managing expansive agricultural projects means it starts from a baseline of limited on-ground capabilities.

For a capital allocator like Danantara — tasked with balancing strategic goals against financial discipline — this reality naturally influences where Agrinas falls in the investment priority list.

Project & Pre-FS Economics

Much of the current debate hinges on the pre-feasibility studies (pre-FS) that Agrinas has reportedly submitted multiple times to Danantara. These documents should, in theory, provide decision-makers with a clear view of the project’s viability, financial returns, and broader economic impact. Yet public reporting on these pre-FS submissions reveals gaps in transparency. We have not seen key metrics such as:

- Internal Rate of Return (IRR) — a cornerstone indicator for investment decision-making.

- Total project cost structure — essential for evaluating funding requirements and capital efficiency.

- GDP multiplier effect — to quantify how each rupiah invested translates into broader economic output.

- Job creation potential — critical for projects tied to political and social mandates.

Without these figures in the public domain, it’s impossible to assess the economic attractiveness of Agrinas’ proposal relative to the other projects in Danantara’s pipeline. From a portfolio management perspective, this lack of clarity can delay approvals — not because the project is unworthy, but because competing proposals may present stronger, more measurable returns on both financial and strategic fronts.

Broader Food Estate Context

It’s also important to remember that the food estate program is not a vacuum. Agrinas is far from the only actor in this space. The Ministry of Agriculture, along with other SOEs, has been driving large-scale agricultural initiatives from the beginning of president prabowo presidency.

This year, Indonesia is on track to achieve its food self-sufficiency (“swasembada pangan”) target, thanks to efforts from multiple players across the value chain — from seed producers and irrigation developers to logistics providers and commodity buyers.

In such a landscape, Danantara is not the sole guardian of the food sovereignty agenda. This reduces the urgency to fast-track Agrinas compared to other sectors where there are no established players and where Danantara’s capital could serve as a first-mover advantage.

This doesn’t diminish the importance of agriculture; rather, it reframes the question: should Danantara lead in a space where capable actors already exist, or should it deploy its limited early-stage capital to areas with unmet needs and high strategic leverage?

Danantara’s Current Focus: SOE Restructuring

Danantara is not operating with a clean slate. At its inception in March 2025, it inherited hundreds of portfolio companies from various SOEs. Many of these entities come with legacy inefficiencies, governance issues, and capital structures that require significant restructuring before they can contribute meaningfully to the portfolio’s value.

The leadership is therefore managing a dual agenda: building Danantara’s identity as a sovereign capital institution while executing deep governance reforms and capital optimization efforts across inherited assets.

This is not merely administrative housekeeping — it’s about ensuring that each subsidiary meets governance standards, aligns with national strategy, and is capital-ready for future investment. These restructuring demands consume not only financial resources but also significant management bandwidth, inevitably influencing the timing and sequencing of new project approvals.

Danantara’s Priority & Project Selection Mechanism

Understanding Danantara’s investment decisions requires looking at its capital allocation framework. As with any rational investment institution, projects are prioritized based on a combination of:

- Value creation potential — both financial returns and strategic national benefits.

- Readiness — how soon a project can move from approval to execution.

- Strategic impact — alignment with broader national goals, from GDP growth to sectoral resilience.

In its formative years, Danantara is focusing on quick-win, high-ROI investments that can establish its credibility among stakeholders, including government ministries, co-investors, and the public. Projects with low IRR or overlapping mandates are not necessarily rejected — they are sequenced for later, when institutional capacity, political capital, and partnership ecosystems are stronger. This sequencing reflects a commitment to capital discipline and timing over symbolic or politically driven launches.

Conclusion: A Question of Timing, Not Relevance

The debate over Agrinas’ funding is not a binary choice between supporting or abandoning food security. It is a question of capital sequencing in a multi-priority environment.

Danantara’s leadership must weigh each project against a crowded pipeline, a finite early-stage budget, and the need to prove itself as a disciplined, value-driven institution. For Agrinas, this may mean taking a back seat in the short term while continuing to refine its proposals, strengthen its operational capacity, and position itself within the broader food estate ecosystem.

If viewed through this lens, the delay in funding is not necessarily a symptom of bureaucratic inertia. It could just as well be the hallmark of a capital allocator determined to ensure that every rupiah deployed delivers the maximum strategic and financial return — for both the institution and the nation it serves.