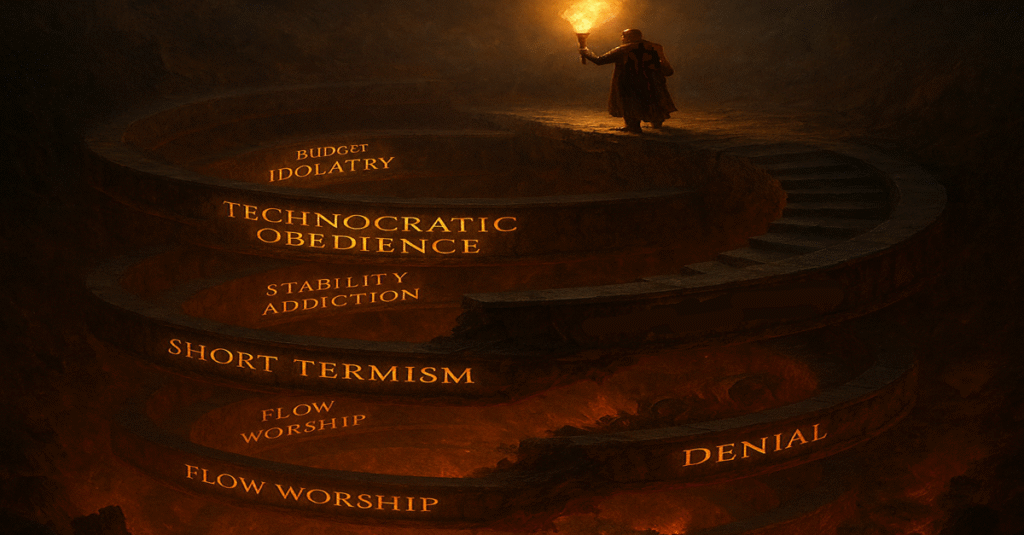

“Economists built a spiral of sins. Capital Architecture is the torch out of their darkness.“

Abstract

Indonesia’s economy remains trapped in outdated doctrines defended by hundreds of economists who mistake debt, budget absorption, and flow metrics for progress. Their “seven demands” recycle the same prescriptions that built stagnation. This paper exposes the Seven Sins of Economists—debt fetish, budget idolatry, technocratic obedience, stability addiction, short termism, flow worship, and denial—and shows how these habits erode sovereignty. In contrast, Capital Architecture reframes economics as a tool of power, aligning fiscal design, credit allocation, and national assets into a compounding strategy. To rise beyond the five percent trap, Indonesia must abandon orthodoxy and embrace sovereign capital.

The Sin

Indonesia continues to be shaped by a small circle of economic authorities whose voices, frameworks, and playbooks have dominated the national agenda for decades. These economists claim expertise over growth, fiscal policy, and national planning, yet the outcome is unmistakable: the country remains trapped in the five percent growth cycle. As of Q2 2025, Indonesia’s economic growth was 5.12% year-on-year, in line with its decade-long average, while official forecasts for 2025–2027 anticipate only modest improvements to 4.8–5.2% annually—well below the trajectory required for rapid development or genuine escape from the middle-income trap.

Instead, Indonesia faces mounting debt, persistent unproductive spending, and an economic engine that lacks resilience and sovereignty. The irony is stark: many who now advocate for reform once shaped, defended, and normalized the country’s vulnerable foundations. Their recurring “seven demands” to government may sound reformist, but these prescriptions distract from the deeper reality. The true source of stagnation is not simply what government has failed to do, but in the systemic errors and blind spots perpetuated by economists themselves

1. The Sin of Debt Fetish

Indonesian economists have long promoted the idea that debt markets fuel national development, repeatedly celebrating bond issuances, sovereign credit ratings, and external borrowing as evidence of economic progress. This approach has led to a heavy fiscal burden: by the end of 2024, government debt stood at 39.2% of GDP, totaling over IDR 8,300 trillion (USD 548 billion). External debt alone grew 6.75% year-on-year to USD 435.6 billion in mid-2025, with government foreign debt up nearly 10% annually. The impact is clear: the government now devotes more than one fifth of annual revenue to interest payments and debt service—estimated at 13–20%, crowding out productive investment in health, education, and infrastructure.

Rather than constructing endogenous engines of national wealth, Indonesia remains exposed and dependent on external financing. The continual fetishization of debt has failed to produce sustainable, sovereign growth, instead creating economic vulnerability and restricting fiscal space for future generations.

2. The Sin of Budget Idolatry

For years, ministries and agencies in Indonesia have been conditioned to worship budget absorption rates as the primary measure of success. Rather than value creation or the buildup of strategic assets, leaders and technocrats were evaluated on their ability to ensure that at least 95% of the annual budget was spent by December 31st—a ritual praised as efficiency in official reports and audits. In practice, this obsession led to systemic waste and misallocation, with resources rushed out the door for short-term spending rather than long-term investment. For example, in 2023, absorption rates were consistently reported above 95% across central government agencies, despite key infrastructure outlays lagging behind and persistent gaps in service delivery.

Critical sectors like infrastructure and healthcare suffered from this mindset. In 2023, only 76% of allocated infrastructure funds were actually utilized, delaying strategic projects, while 30% of regional healthcare budgets remained unspent due to procedural bottlenecks. The result: Indonesia circulated its budget as cash flow, not capital, reinforcing a system of continuous spending without compounding national wealth. The idolatry of absorption turned the state into a spender—not an investor or builder of durable prosperity

3. The Sin of Technocratic Obedience

Since the New Order era, Indonesia’s economic management has been dominated by a cadre of technocrats largely educated abroad, many of whom trained in leading Western universities such as the University of California, Berkeley, MIT, and in Europe. These technocrats, often referred to historically as the “Berkeley Mafia” or “UI-Gadjah Mada Mafia,” formed the backbone of economic policymaking under President Suharto and beyond. Their education and professional experiences aligned closely with the frameworks of international institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF), World Bank, and Asian Development Bank.

This cohort prioritized economic stability—balanced budgets, inflation control, and external debt discipline—above national sovereignty or an assertive economic role for the state. They framed compliance with external benchmarks as central to Indonesia’s development mission, favoring free market rules, deregulation, and integration into the global economy. What was lost amid this technocratic orthodoxy was the idea that economics should serve as a tool of national power and strategic sovereignty.

The consequence is that Indonesia’s economic future imagination was outsourced to external templates. Strategic sectors such as digital advertising and financial infrastructure have remained dominated by foreign actors. For example, over 70% of Indonesia’s digital advertising spending flows to US-based platforms like Google and Meta, reflecting the continued foreign grip on critical digital infrastructure. This external dominance underscores the erosion of sovereignty born from decades of obedience to external frameworks rather than cultivating homegrown economic power.

4. The Sin of Stability Addiction

Economists in Indonesia have long promoted the belief that economic volatility is to be feared and strictly avoided. This led to a rigid adherence to deficit caps, inflation targeting, and conservative fiscal rules, which became treated as almost sacred doctrines within policymaking circles. Stability was relentlessly worshipped as the highest virtue, while true economic resilience and adaptability were largely neglected.

When global shocks like the COVID-19 pandemic struck, Indonesia found itself with minimal sovereign buffers or antifragile mechanisms in place. The country was forced to respond in an ad hoc, reactive manner, scrambling to contain successive crises without pre-designed tools for robust recovery. Many of the fiscal and monetary policies prioritized during the New Order and subsequent administrations focused on financial discipline rather than strategic shock absorption or crisis preparedness.

By treating risk as an enemy rather than as a resource to be managed and designed for, economists inadvertently left the nation fragile. Stability addiction—excessive caution and rigid fiscal orthodoxy—is not strength but weakness masked by the illusion of prudence. This fragile foundation exposes Indonesia to unnecessary vulnerabilities in an increasingly complex global environment

5. The Sin of Short-Termism

Economic planning in Indonesia has long been shackled to the rhythm of five-year political cycles. Every presidential or legislative election triggers a new reset, spawning fresh plans and shifting priorities. This cyclical nature interrupts the possibility of long-term compounding growth and sustained strategic development.

Infrastructure projects typically get planned with horizons rarely exceeding twenty years. This is in stark contrast with countries like China and South Korea, where multi-decade strategies are the norm and serve as frameworks for consistent investment and institutional continuity. For example, China’s Belt and Road Initiative and Korea’s industrial development plans extend well beyond 20 years, enabling sustained infrastructure and industrial transformation.

The frequent leadership turnover in state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and ministries exacerbates this problem, undermining institutional memory and weakening the capacity to see projects through to completion. Studies show SOE executives in Indonesia often serve terms averaging just 2.5–3 years—much shorter than the natural lifecycle of infrastructure and strategic projects.

Economists in Indonesia have normalized this short-term operational logic, framing it as democratic accountability and flexibility. Yet in practice, it prevents the building of enduring economic power, perpetuating a cycle of stop-start development incompatible with the compounding nature of modern economic growth.

6. The Sin of Flow Worship

Economists have long treated gross domestic product (GDP) growth as the ultimate measure of national success. Year after year, they celebrate Indonesia’s steady 5% growth rate as a victory, while overlooking a more critical metric: national wealth per capita. Between 2010 and 2022, Indonesia’s GDP per capita increased by only about 1% annually in real terms, rising from roughly USD 3,200 to USD 4,780—far slower than many comparator countries.

Meanwhile, comprehensive wealth growth—which includes produced capital, human capital, natural capital, and financial capital—has likewise failed to translate into equivalent income gains. Natural resource wealth and raw commodity flows such as nickel and palm oil exports inflate GDP numbers, but the real value-added margins are largely captured abroad through foreign-owned downstream processing and global market channels. In digital markets, over 70% of Indonesia’s advertising revenue goes to foreign platforms, further illustrating this trend.

By focusing narrowly on GDP flow metrics rather than building and retaining stock of wealth, economists have mistaken motion for progress. The country’s rate of return on wealth has declined, signaling that growth does not equate to sustainable prosperity. This flawed focus obscures the need for policies that accumulate real, durable national wealth over time.

7. The Sin of Denial

Faced with the consequences of their own doctrines, many economists now lament that the state has become too dominant, that sovereign capital vehicles like Danantara distort markets, and that populist spending is to blame for Indonesia’s economic malaise. They point fingers at others—politicians, populists, or foreign actors—while refusing to acknowledge that their own entrenched frameworks created the stagnation in the first place.

These frameworks—debt dependence, budget absorption obsession, technocratic obedience to external orthodoxy, stability addiction, short-term planning, and flow worship—have collectively limited Indonesia’s capacity for durable growth and sovereignty. Their denial blinds them to the structural reforms needed and traps them within the very orthodoxy that caused the crisis.

As the economy slows and the social fabric strains—evident in growing protests, rising layoffs, shrinking middle class, and public discontent—this intellectual recalcitrance jeopardizes the nation’s ability to see a new path forward. Until economists break free from these paradigms and embrace sovereign capital architecture as a foundational doctrine, Indonesia risks prolonging economic weakness and social instability.

Together, these seven sins explain why Indonesia is trapped in a legacy system that cannot scale. Debt has become a burden, budgets have become rituals, sovereignty has been traded away, stability has been mistaken for strength, planning has been reduced to five year resets, growth has been measured in empty flows, and denial blinds the intellectual class. The “seven demands” of economists are not solutions. They are distractions. They recycle the same prescriptions that failed in the past.

Indonesia! The Way Forward

The way forward for Indonesia is not to listen to another sermon from those who authored the broken engine. The way forward is to embrace capital architecture. This means treating the state as a strategic investor, ministries as capital deployers, and national planning as a compounding portfolio. It means shifting from debt as fuel to equity as leverage, from budget absorption to sovereign return on investment, from flow obsession to stock accumulation, and from crisis aversion to antifragility by design. It means building to own, not just to spend.

For Indonesia, the task ahead is clear. The old economic model has run its course. The seven sins of economists must be acknowledged and left behind. The future lies in constructing a sovereign capital doctrine that aligns economics with power, resilience, and long term prosperity. If Indonesia dares to step beyond the comfort of outdated orthodoxy, it can rise as a true capital architect in Southeast Asia and beyond. The time to build has come.